In 2024, I sold my collection of a few hundred vinyl record albums to Jonathan Sandler of Village Vinyl & Hi-Fi in Coolidge Corner. They were mostly jazz albums I'd bought in the 1970s and 1980s, including quite a few older albums I'd picked up in used record bins during those pre-CD years.

The covers of the album, as well as the music on them, carried a lot of sentimental value for me. But I hadn't actually owned a turntable for years, and I was glad that, in addition to providing me some extra cash, the music would find new owners/listeners, especially amid a growing appreciation for vinyl.

I also gave Jonathan a printout of a 1955 Brookline Citizen ad for Rhythm Row, a record store in the exact same Harvard Street storefront to which he moved his then year-old shop -- originally in Brookline Village -- in 2018.

|

| Brookline Citizen, January 5, 1955 |

307 Harvard Street is one of a row of single-story storefronts built just south of Babcock Street in 1928. Tenants over the years have included various restaurants and clothing shops. The Rhythm Row music shop was there for just a couple of years in the mid-1950s.

(The 1955 ad highlighted a visit from noted jazz disc jockey

"Symphony Sid" Torin. (One the albums I sold, by jazz singer King Pleasure, included a song --

"Jumpin' With Symphony Sid" -- with music by Lester Young and lyrics by Pleasure.)

The presence of two record shops in the same spot six decades apart is mere coincidence, one Jonathan had been unaware of. But it did set me off on a journey to learn about the history of music stores in Brookline, the subject of this extended post.

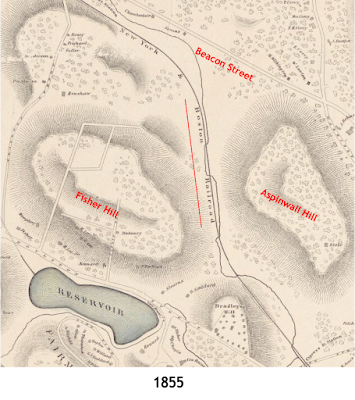

Edison and Sound Recording

Thomas Edison's earliest work with sound recording caught the attention of Brookline. As early as 1878 the Brookline Chronicle carried a query from a reader asking "Can you tell me anything about the early life of Edison, the inventor of the phonograph?" By the late 1880s, Edison had moved from cylinder recordings to discs and the Brookline papers were paying attention.

In February 1889, a brief item in the Chronicle noted an entertainment at the Corey Hill home of Jerome Jones. "The subject," reported the paper, "was Edison's inventions, with both the phonograph and the gramophone instruments and an expert to demonstrate the marvelous power of them."

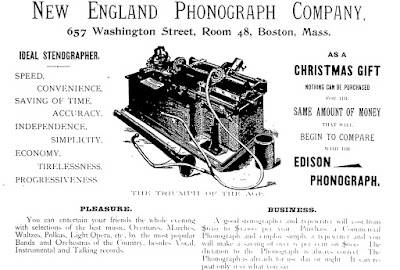

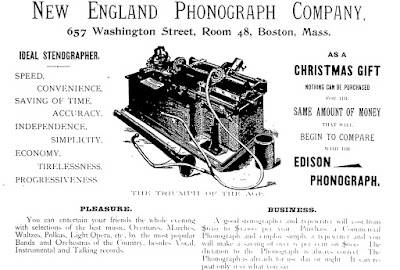

Newspapers, including Brookline papers, continued to report on Edison's technical innovations, and advertisements promoting commercial applications were not far behind. In December 1893, the Chronicle carried an ad from the New England Phonograph Company in Boston promoting their new device as an "ideal stenographer" but as also promising that

"As a Christmas gift nothing can be purchased for the same amount of money that will begin to compare with the Edison Phonograph."

|

| Brookline Chronicle, December 16, 1893 (Click ad for larger view) |

The ad called the new device "The Triumph of the Age." In addition to using it for business, it said,

"You can entertain your friends the whole evening with selections of the best music. Overtures, Marches, Waltzes, Polkas, Light Operas, etc. by the most popular Bands and Orchestras of the Country besides Vocal, Instrumental, and Talking records."

Public Programs

There were examples noted in Brookline newspapers in the 1890s of public programs using the phonograph to present sermons, speeches, election returns, and music to live audiences in town. By the fall of 1899, it seemed the gramophone craze at had truly taken off in Brookline.

See, for example, these notices in the local papers:

|

| Brookline Chronicle, September 30, 1899 |

|

| Brookline Suburban, October 26, 1899 |

|

| Brookline Chronicle, December 9, 1899 |

|

Phonograph Sales Spread

Brookline papers also started advertising sales by Boston stores of phonographs or gramophones for home use, along with records to play on these new machines.

|

| Brookline Chronicle, September 16, 1899 |

|

| Brookline Chronicle, October 21, 1899 |

|

| Brookline Chronicle, June 9, 1900 |

Prices of record players started to drop as manufacturers started to realize they could make bigger profits by selling more records if the cost of the machines to play them on came down.

"It is confidently believed that this substantial price reduction will have the effect of placing gramophones...in the hands of thousands of persons who have hitherto been restrained from purchasing by reason of the comparatively high prices heretofore prevailing," reported the Chronicle. (June 30, 1900)

It was the same principle behind King C. Gillette's sales of razors at low cost with the real money to be made on repeated sales of razor blades. (Gillette, by the way, came up with this idea while living in Brookline in the same period. See

that story in another of my blog posts.)

As early as 1903, one enterprising person took out an ad in the Chronicle offering for sale a phonograph with a collection of "about fifty records."

|

| Brookline Chronicle, November 21, 1903 |

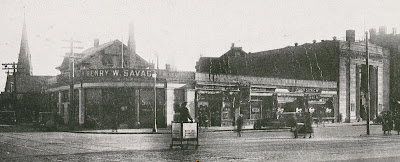

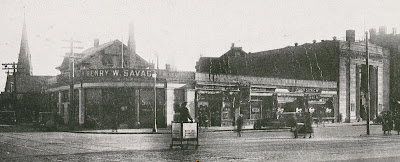

A little more than two years later, Henry Savage's real estate concern, with a branch in Coolidge Corner, advertised listening rooms "to hear and select your Phonograph Records."

|

| Brookline Chronicle, January 27, 1906 (Click image for larger view) |

"Under these new conditions selecting records becomes a pleasure," said the ad. "We sell every good make record and machine. Edison, Columbia Disc and Cylinder, Victor, and American Disc."

|

| Henry Savage's real estate office stood at the southwest corner of Beacon and Harvard Streets. The building was later torn down and replaced with a new building at the same location. (Click image for a larger view.) |

Four years later, in 1910, Martin Barrett, who had a cigar store on Washington Street where it crosses over the train tracks in Brookline Village, advertised Edison phonographs for sale as a Christmas gift.

|

| Brookline Press, December 24, 1910 |

Four years after that, the business, taken over by John J. Williams, gave equal prominence to cigars and phonographs in its listing in the 1914 town directory...

...while also hosting a record exchange that local people could take part in.

In 1915, a new store called the Brookline Talking Machine Shop opened at 1336 Beacon Street, in a new building called the Pierce Block, just west of the S.S. Pierce store. (That storefront is now home to a branch of the national-wide hair-cutting chain Supercuts.)

|

| Brookline Townsman, July 10, 1915 |

The new business advertised the sale of both records and record players.

|

| Click image for larger view |

Local organizations, in Brookline and elsewhere, starting acquiring records and record players.

|

Brookline Chronicle, July 15, 1919

|

|

| Brookline Chronicle, June 18, 1921 |

|

| Brookline Chronicle, April 1, 1922 |

Brookline Record Stores

Recorded music may have made its first appearances in Brookline through special event announcements and ads from Boston-based music stores. But stores selling records soon began to appear in town.

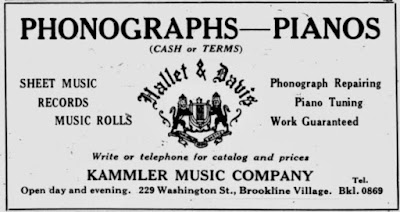

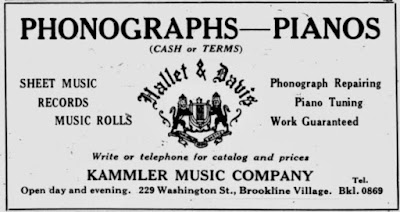

In December 1922, a store called Kammler & Hamilton at 229 Washington Street in Brookline Village (the storefront is now the Shared Tea) was billing itself as "Brookline's Exclusive Music Store," offering "all the latest 'Hits' to select from."

|

| Brookline Chronicle, December 12, 1922 |

Chester E. Kammler would run the Kammler Radio Company until his death in 1935. (His original partner, Hamilton, was with him for just the first year.) Born in 1892, the son of German immigrants, Kammler had worked for a Boston-based piano manufacturer before serving in the army in World War I.

Kammler would continue sell records, along with phonographs, sheet music, and other items in the same location for a little over a decade.

|

Brookline Chronicle, November 24, 1923

|

|

| Brookline Chronicle, December 16, 1926 |

A 1932 Chronicle article -- "Kammler Music Company Celebrate Their Tenth Year Here" -- noted that

"The phonograph is well represented through a complete stock of Victor, Columbia and Brunswick recordings of the latest dance music and vocal selections."

Chester Kammler died in November 1935. The store remained oven for a short time after his death, as seen in the ad below, but soon closed.

|

| Brookline Chronicle, February 6, 1936 |

There were many more Brookline stores selling records over the next half-century, (See the end of this post for ads and articles about many of these.) But by the 1990s, cassettes and CDs had far overtaken LPs as the most popular format for recorded music, as seen in this chart produced by Recording Industry Association of America.

|

| (Click image for larger view) |

The rise of online music formats led to a further decline in all physical media. (According to one news account, more than three thousand record stores closed their doors in the United States between 2003 and 2008.)

The Vinyl Revival and Village Vinyl & Hi-Fi

The decline of vinyl records and record shops was closely followed in the mid-2000s by a movement that's been called the

Vinyl Revival, And Brookline's Vintage Vinyl & Hi-Fi, with which I began this post, is a successful part of the movement, as

featured recently in the Boston Globe.

"This Coolidge Corner spot" wrote the Globe "is the place to find that record you never knew you needed until you got there."

|

| Boston Globe, July 2025 |

Vintage Vinyl & Hi-Fi began in a basement storefront at 58A Harvard Street in Brookline Village in 2017.

|

| Vintage Vinyl & Hi-Fi in its original Brookline Village basement location at 58A Harvard Street where it opened in 2017. (Image via Google Maps) |

|

| Jonathan Sandler in his original Brookline Village location at 58A Harvard Street in 2017 |

In 2018, Village Vinyl & Hi-Fi moved to its current location in Coolidge Corner. The store expanded in 2024, taking over the adjacent storefront formerly occupied by branches of flower and plant seller Kabloom and then Vom Fass, a German-based seller of gourmet olive oils and other food products.

|

| Village Vinyl & Hi-Fi in 2020, before it expanded into the adjacent space previously occupied by Kabloom and then Vom Fass |

|

| Village Vinyl & Hi-Fi in 2025 after expanding into the adjacent storefront |