Monday, December 19, 2022

Introducing "This Week in Brookline History"

Once a week, TWIBH will present brief summaries of four events that occurred in the past on that week's dates.

The summaries will be accompanied by photos, maps, sketches, news headlines, or other illustrations. Links to further information, where available will also be included.

An example, covering the week of January 1st to January 7th, is previewed below, but new weeks' entries will be on a separate site beginning January 1st.

To receive these weekly TWIBH posts by email, go to https://bit.ly/brooklinehistory and submit your name and email address via the form. (You can use the same form to subscribe to the more sporadic posts from this Muddy River Musings blog, if you are not already subscribed.)

Wednesday, December 14, 2022

Harvard Street, Coolidge Corner: 1912 & 1937

Two of the busiest periods of commercial development in Coolidge Corner took place in the 1910s and 1920s. Perhaps no two photographs demonstrates this change better than these two images of the same stretch of Harvard Street, one from c1912 and the other from 1937.

|

| West side of Harvard Street between Beacon Street and Babcock Street (offscreen to the left), c 1912 Postcard view (Click on this and all images for larger views) |

|

| Same view, 1937 Photo courtesy of Brookline Preservation Department |

| S.S. Pierce Building and Beacon Universalist Church, c1906 |

S.S. Pierce Building and Coolidge Corner Theatre, 1937 and 1970s

|

| Closer view of this stretch of Harvard Street |

|

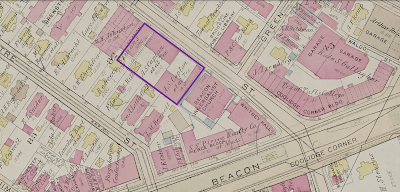

| 1913 atlas view (Yellow buildings are wood-frame structures; pink buildings are brick.) |

|

| 1927 atlas view |

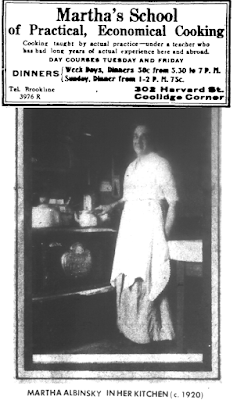

Even before being replaced, some of these and other houses on Harvard Street were put to new uses. The house at 302 Harvard, for example, became a boarding house, lunchroom, and cooking school run by a German immigrant named Martha Albinsky. Her daughter, Gertrude (Albinsky) Millett, wrote about it in the Brookline Chronicle half a century later and included a photo of her mother in her kitchen. (1976 article, at bottom of linked page.)

|

| Ad from 1918 and 1920 photo from 1976 article both from the digitized newspaper collection of the Public LIbrary of Brookline |

"The house my mother rented [wrote Millett in 1976] was very suitable to our purpose. It had been used as a party house by Rose Gordon and the large front room was ideal for a public dining room while the rest of the house could be used for boarders...But my mother's desire was to have a real dining room with homecooked meals for it was easy enough for her to cook for five or 20..."

"The homecooked dinner consisting of soup, main course, dessert, tea or coffee was 50 cents, and everyone enjoyed it, particularly the fresh-baked Parker House rolls which were my mother's specialty."

"The dining room was a success from the start, serving anywhere from 10-15 customers every night."

Houses across the street were also put to new uses before being replaced by retail buildings. The house at 299 Harvard became the Coolidge Corner Branch of the Brookline Library, while the house next to it at 303 became a funeral home. Both of these can be seen in the full version of the c1912 photo below. (Streetcar tracks are also gone, while cars are parked at the curb in front of the 1937 stores.)

|

| Full postcard view of Harvard Street looking south from near Babcock Street, c1912 (Click for larger view) |

Monday, October 10, 2022

Booksmith Makes History in Coolidge Corner

On Friday, Brookline Booksmith will mark a new stage in its 61-year tenure in Brookline with a ribbon-cutting and other festivities to celebrate the latest expansion of the venerable bookstore.

https://www.brooklinebooksmith.com/event/brookline-booksmith-ribbon-cutting-celebration

Like the Coolidge Corner Theatre (also expanding), its neighbor across Harvard Street, Booksmith is an icon and an anchor -- socially, culturally, and economically -- of its neighborhood, serving the local community and drawing visitors and customers from throughout the region.

The new addition to the store, incorporating the space formerly occupied by Dependable Cleaners, gives Booksmith an unbroken streetscape between Starbucks and the recently opened Mecha Noodle Bar at the corner of Green Street.

In honor of the occasion, I've taken a look at the long history of the row of storefronts now occupied by Booksmith, going back more than 110 years to a brick commercial building erected at 279 Harvard Street in 1910. That building was the first occupied by Paperback Booksmith in 1963 after two years at 271 Harvard (now game Stop)..

Among the previous occupants of that space and the other storefronts now part of Booksmith have been:

- The Racheotes Brothers' Faneuil Hall Fruit Store at 279 Harvard Street in 1911 and later at 281 and 283 Harvard

- A.J. Landy & Co., the first kosher delicatessen in Brookline, which opened at 279 Harvard in 1914.

- A pair of grocery stores that competed, side by side in the 1940s: Finast, or First National Stores, at 279; and Stop & Shop, extending south from Green Street at 285.

|

|

| This First National Stores, or Finast, supermarket, seen here in an ad for a 1947 remodeling, was in business at Booksmith's original location from the 1920s through the 1950s. |

There have been many others, too, including a florist, a hairdresser, an upholsterer, a rug dealer, a bakery, a drug store, a milliner, a women's clothing store, and several more over the years, all in spaces now occupied by Booksmith.

A few more ads and images from the pre-Booksmith days are below. I'll have more, including more recent occupants, in a later post.

| ||

| Fine the Florist, 279 Harvard Street, 1922 ad |

|

| Baker Apothercary, 281 Harvard Street, 1948 ad |

|

| Schrafft's, 283 Harvard Street, 1940 ad |

| |

| Adeles Hats of Distinction, 283 Harvard Street, 1936 ad |

|

| Schulte-United Junior Department Store, 285 Harvard Street, 1929 ad. (The company, which made a big splash with full page ads like this, went bankrupt two years later.) |

NOTE: Advertisements are from town directories and Brookline newspapers digitized by the Public Library of Brookline and other sources.

Wednesday, September 14, 2022

3 Doctors & Their 19th Century Brookline Houses

If you stand on the northeast side of Washington Street about halfway

between its intersections with Greenough Street and Weybridge Road

you'll be in one angle of a triangle formed by three Brookline houses

from three different eras of the 19th century.

- #1 -- 26 Weybridge Road -- is in the style of the Colonial Revival of the late 19th-early 20th century and appears to be the newest of the three but is actually the oldest, built in 1822. It was redesigned in 1868 and again, as a Colonial Revival home, in 1922. A more recent (2016) renovation restored elements of that 1920s design that had deteriorated or been removed in later years.

- #2 -- 447 Washington Street -- was built smack dab in the middle of the century, c1850.

- #3 -- 432 Washington Street has the look of a pre-Revolution house, but only because it was designed as a replica of John Hancock's Beacon Hill mansion, built by his uncle in the 1730s and torn down in 1863. It is actually the newest of the three, built in 1895.

When the most recent of these -- the Hancock replica -- was built, there was very little around them on the now densely built-up section of this busy thoroughfare between Brookline Village and Washington Square.

|

| The three houses shown on the 1900 Brookline atlas |

All three houses were originally the homes of doctors and their families. But the three doctors -- Charles Wild, Charles Wheelwright, and Benjamin Blanchard -- were as different from one another as are their still-standing houses.

|

| Left to right: Drs. Charles Wild (1795-1864), Charles Wheelwright (1813-1862), and Benjamin Blanchard (1856-1921) |

The Wild-Sargent House (1822)

The

oldest of the three houses, now known as the Wild-Sargent House, was

built in 1822 for Dr. Charles Wild and his wife Mary Johanna (Rhodes)

Wild. There are no known photographs of the house showing how it

originally looked. The oldest known photo shows the house in 1868, after a

post-Civil War renovation by it's fourth owner.

|

| Today's

26 Weybridge Road as it appeared from Washington Street in 1868 after a

major redesign. It retained this design for more than 50 years. |

The house was remodeled again as part of the Blake Park development of the 1920s.

Image credit: Public Library of Brookline |

Charles Wild (1795-1864) was born in Boston, graduated from Harvard in 1814, and was granted a medical degree in March 1818. (His dissertation was on delerium tremens.) Harriet Woods in her Historical Sketches of Brookline, published in 1874, presented a lengthy profile of Dr. Wild.

Those who can remember the doctor in his prime [wrote Woods], can well recall his tall, well-formed figure, his firm tread, his deep voice which seemed to come from cavernous depths, and eyes which seemed to look from behind his spectacles into and through one.

Woods described the doctor's typical way of announcing his arrival to see a patient:

He had a breezy way of entering a house, stamping off the snow or dust with enough noise for three men, throwing off his overcoat, untying a huge muffler that he wore around his neck, and letting down his black leather pouch with emphasis. There was an indescribable noise he made sometimes with that deep gruff voice of his which cannot be represented in type.

Dr.

Wild, widely respected in town for his knowledge, abilities, and

advice, was skilled in the mixing and administering of potions, in

bloodletting, and in other techniques practiced by the physicians of his

day. In 1839, he became interested in the emerging ideas of homeopathy.

The

second meeting of New England physicians interested in this new kind of

practice took place at the house on Washington Street in 1841. It led

to the formation of the Massachusetts Homeopathic Fraternity.

The

Wilds' second son, Edward Augustus Wild, was also a doctor, until he

lost an arm serving in the Civil War. He later returned to service as a general commanding troops of formerly enslaved

African American soldiers.

For much more on the life of the Wild family in their Brookline home, see the 1851-1865 diary of Mary Johanna Wild, digitized by Boston College and annotated by the Brookline Historical Society.

The Candler Cottage (1850)

In 1847, Mary Johanna Wild wrote to her oldest son, Charles, then in Shanghai where he was engaged in the China trade, that

As I sit at the old desk in the study now, I can look out and count more than 30 new houses put up in the last year.

Three years later, another new house, directly across Washington Street from the Wild house, appeared. A sketch of the house, designed by architect Richard Bond, was included in a book, American Cottage and Villa Architecture. published in 1850. It shows open land around around the house, with Aspinwall Hill rising in the distance on the left.

|

| Image credit: Historic New England |

The first owners of the house were Susan Candler and her brother Dr. Charles Wheelwright. They were joined by Susan's five children, ranging in age from 24 to 11, and two Irish-born servants. Susan's husband had died in 1842.

Writing to a nephew in February 1850,

Wheelwright said the family, then living in Boston, was looking to find a

country house to purchase:

We have concluded to seek placdium quietam in rure felice. There we must be near railroad and omnibuses, we must have open fields and sunny hills....We have found a beautiful place exactly eighteen minutes distant from Worcester Railroad Depot in Boston. It is nearly opposite the Aspinwal place on the road from Brookline to Brighton. It is very expensive but land is increasing in value so rapidly that if we can get it at a fair market price we think we shall buy, Susan and myself conjointly.

Family members, wrote Wheelwright, had visited the house and were much pleased with it:

It is really a beautiful place, well back from the road. A cottage with two arched towers and quite high and really airy chambers, fifteen rooms in all, barn, etc., and 300 fruit trees. I shall offer 9500 dollars and fear it will not bring it. I will be sorry to lose it as it offers so many facilities and conveniences not to be found in other places.

|

| Dr. Charles Wheelwright |

In the end, they were able to purchase the house and land for $8,500.

Charles Wheelwright was born in Boston in 1813. He graduated from Harvard in 1834 and earned a medical degree there in 1837. In 1839, he joined the U.S. Navy as a surgeon and would remain in naval service for the rest of his life, serving in the Atlantic, the Pacific, and the Gulf of Mexico. In 1859, he was part of Commodore Matthew Perry's expedition to Japan.

At the outbreak of war, Wheelwright was serving in the Brooklyn Navy Yard on a board examining men for their fitness to serve in the Navy. Despite his own poor health, he applied for active duty. He served in Virginia and, later, as fleet surgeon for the Gulf Fleet. He was then assigned to a hospital near the mouth of the Mississippi River in Louisiana, treating troops of the River Squadron.

Suffering from poor working conditions, exhaustion, diarrhea, and general poor health, he died of disease in Pilot Town, Louisiana, on July 30, 1862. He was 49 years old. He is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. The house remained in the Candler family through the end of the war.

The Blanchard House (John Hancock House Replica) (1895)

In 1863 the Beacon Hill land containing the former home of John Hancock was sold. Plans to move the house to the Back Bay fell through. Protests against its demolition went unheeded. In August the house was demolished, replaced by two townhouses. (In 1917, the townhouses were replaced by an extension to the State House.)

The

loss of the former home of one of Boston's and the nation's Founding

Fathers was a factor in the growth of the historic preservation

movement. In the decade after its demolition, another landmark of the

Revolution, the Old South Meeting House, which had barely survived the

Great Boston Fire of 1872, was saved from demolition after the church

moved to a new building in the Back Bay.

At the World's

Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, the Massachusetts State

Building, designed by the noted Boston firm Peabody & Stearns, was

modeled after the demolished Hancock mansion. At the dedication of the

building in October 1892, Massachusetts governor William Russell spoke

of the symbolic importance of the design:

I think there is something grand and most instructive in these historic buildings. They link the past with the present, with lessons of patriotism, suffering and sacrifice; they speak of men who were patriotic, events which were epoch making and the beginning of a great nation....

This building comes close to the heart of Massachusetts, not merely because it is beautiful in design and correct in proportion, but because it speaks of Hancock, his life and his services, and recalls a great agitation, a struggle for liberty and independence, in which Massachusetts and her ideas were leading to form and develop a great and majestic republic

|

| The Massachusetts building at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, as shown in Campbell's Illustrated history of the World's Columbian Exposition (1894) |

The Massachusetts building was itself demolished after the Exposition. (Another building from the Exposition, built for the Van Houten Cocoa Company as a replica of a 16th century Dutch town hall, was purchased by a Brookline resident, Charles Appleton. It was taken apart, brick by brick, and reconstructed on a new street in Brookline. Now known as the Dutch House, it stands on Netherlands Road, near the Muddy River.)

Two

years after the end of the Exposition, architect Joseph Everett

Chandler designed a new home, also modeled on the Hancock mansion, at

the corner of Washington and Greenough Streets in Brookline for Benjamin

and Clara Blanchard.

Chandler was an important figure in the Colonial Revival style of architecture that flourished in the U.S. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Blanchard House was the first of four houses he designed that were modeled on the Hancock house and the one that most closely followed the design of the original.

|

| This photo and floor plan were included in Joseph Chandler's 1916 book The Colonial House |

The original stone facade, which Chandler described as "the best of Colonial stonework," was replicated in wood as closely as possible.

The

other Chandler houses modeled on the Hancock house include 58 Allerton

Road in Brookline and homes in Weston and in Chandler's native Plymouth.

He also designed several other buildings in Brookline, including an art

gallery for the Blanchards' neighbor Desmond Fitzgerald, now the Church

of Christ at 416 Washington Street.

Chandler

is probably best known for his restoration of historic buildings,

including the Paul Revere House in the North End of Boston and the House

of Seven Gables in Salem. (For much more on Chandler and his work, see his 1922 book The Colonial House.

Another still-standing building modeled on the Hancock mansion -- though not designed by Chandler -- is the stone headquarters of the Ticonderoga Historical Society in Ticonderoga, NY, built for the New York State Historical Society in 1926.

|

| Photo credit: HUP Blanchard, Benjamin S. (1). Harvard University Archives. |

Benjamin

Seaver Blanchard graduated from Harvard in 1877 and from Harvard

Medical School in 1882. He practiced for a year in Roxbury where, as he

later wrote,

[I] had a fair amount of work, little pecuniary recompense, but plenty of blessings, some curses, and good opportunities to study human nature.

Blanchard came to Brookline in 1883. He lived and had an office at 18 Davis Avenue in Brookline Village. In 1887, he married Clara Fessenden Barnes, and eight years later they bought land from the Blake estate to build their new house.

Blanchard

maintained his medical practice out of the Washington Street house.

He was also active in town affairs, serving as a Town Meeting Member and

a member of the school committee, and as a medical inspector for the

schools and the Gymnasium and Baths Committee.

He was a leading

figure in the town's efforts to combat various epidemics and threats to

community health through inspections and vaccinations. Blanchard died at

home of rheumatic fever in 1921. He was 64 years old.

Saturday, July 23, 2022

Brookline's Oldest Restaurant

The Busy Bee Restaurant on the north side of Beacon Street near its intersection with Carlton Street is Brookline's oldest existing restaurant.* It opened in 1955 and was taken over by the current owners a dozen years later.

| |

| Advertisement announcing the grand opening of Busy Bee. Brookline Citizen, April 14, 1955, p7. |

|

| Busy Bee Restaurant, 1046 Beacon Street, today (from Busy Bee website) |

The commercial building (1040-1054 Beacon) housing Busy Bee marked its 100th anniversary last year. Busy Bee's location in the middle of the block of storefronts was the site of a variety of businesses -- including one featuring miniature bowling! -- before the first of a series of short-lived restaurants opened there in 1949.

|

| This article and advertisement for miniature bowling at 1046 Beacon Street ran in the Brookline Citizen on February 11 and February 18, 1938. (Click for larger view) |

| Advertisements for restaurants that preceded Busy Bee at 1046 Beacon Street: Danny's (1949); Margo's (1950); and Fitzpatrick's (1952) (Click for larger view) |

But while Busy Bee is the oldest existing restaurant, there is one Brookline storefront that has been a restaurant location -- though not the same restaurant -- for even longer than has 1046 Beacon Street. In fact, this location will mark 100 years of continuous operation as one restaurant or another in 2023.

Can you guess where it is? (Hint: You may not think of this address as being in Brookline. See the comments below for some guesses, including the correct one.)

Sunday, February 20, 2022

19th Century Tobogganing on Corey Hill

A winter storm in Brookline today brings sledders to local hills, carrying all manner of conveyance for children and adults alike: classic Flexible Flyers; modern plastic models in a variety of shapes and colors; even cardboard boxes and purloined cafeteria trays.

130 years ago, it also brought tobogganers to go whizzing down the most celebrated toboggan run in the Boston area: the steep chutes of the Corey Hill Toboggan Club.

Operating each winter, from December 1886 to February 1895, chutes ran from a clubhouse on Winchester Street across the then undeveloped lower slope of Corey Hill to a spot on Harvard Street approximately where the Chabad Center of Brookline (496 Harvard Street) is today.

A Canadian Import Comes to Brookline

Toboggans – and the word toboggan – originated with indigenous peoples of North America, who used them to transport items across snowy landscapes. Recreational tobogganing began in Canada, most notably on Mount Royal in Montreal where the Montreal Toboggan Club opened three slides in 1879.

Tobogganing soon spread across the U.S. border. The Corey Hill Toboggan Club was formed in November 1886, and quickly became known as the best facility in the northeast.

Construction of a clubhouse and chutes began immediately after the formation of the club. The clubhouse stood approximately where 197-199 Winchester Street is today. By December 1886 there were three chutes in place, one of the three starting from a platform at the top of the clubhouse 12 feet above the level of Winchester Street. That made for a rapid 42-foot drop to the level of the meadow that ran to Harvard Street.

In early December, the club successfully petitioned the Brookline Electric Light Company to have poles places along Harvard Street to provide power to light the chutes at night. By Christmas, the electric lights were in place.

When a 300-strong contingent of the Montreal snowshoe and toboggan club Le Trappeur visited Massachusetts in February 1887, members of the three-month old Corey Hill Toboggan Club were their main escort in a large parade through the streets of Boston.

|

| The Le Trappeur club of Montreal marching down Beacon Street in Boston from the State House as shown in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, February 12, 1887 |

A lack of snow prevented the Canadians from trying the Brookline slides, but they did take back to Montreal an oil painting showing two club members, Massachusetts governor Oliver Ames and 20-year old Florence Peck of Boston, flying down the Corey Hill chute on a toboggan. Peck, whose father was on the executive committee of the club, presented the painting to Montreal mayor Honoré Beaugrand at a State House reception.

A month later, several members of the Brookline club visited their one-time guests for the winter carnival in Montreal.

The “Best and Most Expensive” Slide

By the winter of 1887-88, there were at least five toboggan slides in the Boston area. They included a slightly older Brookline club at Wright’s Hill, near Boylston Street and Reservoir Lane, and facilities in Dorchester, Cambridge, and Malden. But, reported the Boston Globe in a lengthy article on tobogganing, “the Corey Hill slide is by far the best and most expensive one.”

The chutes, reported the Globe, were not as long as some of the others in the area, “but the management finds that it is more pleasing to the members to have them short and steep instead of long and gradual.” In fact, wrote the Globe reporter, the Corey Hill chute was the steepest in the country.

|

| Tobogganing on Corey Hill, as seen in a later article in the Boston Globe (January 15, 1893) |

The club grew to more than 300 members that second winter of its existence, including residents of Brookline, Back Bay, and other parts of Boston and neighboring communities. The clubhouse was enlarged to include a waiting room with a fireplace on the lower floor, a smoking room, bathrooms, a kitchen for preparing meals and refreshments, and a storage area for toboggans so that club members did not have to carry them to the site each time.

The chutes themselves had water poured on top of the packed snow where it would freeze and provide a smooth sliding surface. A well was sunk and pipe was laid along the length of the chutes to keep them watered. Innovations in later years includes a tilting platform at the top and a motor-driven return chute to bring toboggans back up the hill for additional runs or storage.

Articles in the Brookline and Boston newspapers described the thrill of taking a toboggan down the Corey Hill chutes. Here’s how the Boston Globe described it in December 1887:

“A push, a rush of cold air, and you fall through space more like a meteor than anything else. It is not a slide; it is a flying hop-step-and-jump to the foot of that 100-foot slope. Even then the speed seems to increase, but the novice feels that the toboggan is sliding over something solid, and that is a crumb of comfort. In quicker time than it takes to read, much less write it, the toboggan flies straight out over the dip or second fall and comes down with a flop, but without wavering in its wild career continues scurrying down the incline.”

Novices, said the Globe, find “their sensations of fright and delight so inextricably mixed that they can’t tell which is uppermost. And the beauty of the whole thing is the sensation does not wear away as your trips become more frequent.”

An 1893 article in the Boston Post, written under the pseudonym “Amy Robsart,” described one woman’s experience going down the Corey Hill chute this way:

“I took a long breath and shut my eyes. – ! – !

There were two consecutive bumps half way down that made me open them, and I saw flying bits of Biela’s comet and thousands of starry dazzlements in a flight through the air. That is probably the nearest I shall ever approximate to flying….

My bangs stood up straight, my hat flapped wildly on the firm pivot of my hat pin, there was a trail of hairpins in my wake.

‘Where am I at?’ I inquired a little ruefully when I had been picked out of the snow and had smoothed my ruffled plumage.

But it was fun!

Fun with the keen edge of fear that gives it the fascination that it is.”

Clothing, Class, and Gender

Toboggans, toboggan slides or chutes, and the thrill of participating were not the only elements of this popular recreational activity to cross the border from Canada. Tobogganing fashion also followed the Canadian model. Members of the Corey Hill club, and other clubs, wore outfits modeled on those of Canadian clubs, with each club having its own colors.

More significant were class and gender elements of tobogganing that were common in Canada and were replicated in Brookline and other American communities. As Canadian scholar Gillian Poulter wrote in a 1999 dissertation (later turned into a book) on sport, spectacle, and identity in Montreal:

“Forming clubs and building slides and club houses was a means by which club members differentiated and separated themselves from the poorer classes. By demarcating specific areas as club property, and by adopting blanket suit costumes, the professional and commercial middle-class tobogganers were in no danger of having to share their slides with ‘the great unwashed,’ who in any case probably had little time and energy to spare for such diversions.”

At Corey Hill, a club membership cost $3, later increased to $5. Club members had to wear their club badge – an example is shown below – to use the toboggan chutes. The club outfits – not required, but common – and the toboggans themselves added additional costs. The club drew members – including at least two Massachusetts governors -- from Brookline as well as the Back Bay and other areas.

|

| Photo courtesy of the Public Library of Brookline |

It’s not known if there were specific ethnic restrictions in the club’s bylaws, but it is worth noting that although Brookline had a substantial, largely working class, Irish-American population by this time there are no Irish surnames shown in the many articles in the Brookline and Boston newspapers that listed officers and participants in the club’s activities

(The Country Club in Brookline, which was started just four years before the Corey Hill Toboggan Club and had its own history of restrictive membership policies, also had its own toboggan slide during this period.)

Men and Women Together on the Slopes

The thrilling ride down a toboggan chute presented opportunities for a kind of closeness not usually considered proper for young couples. As the Toronto literary magazine The Week put it in an 1885 article:

“When Florence or Charlotte has to be tightly encircled in the grasp of an admiring pilot, down the glittering descent, the pair feel the mutual dependence and responsibility, which often leads them to courtship in earnest.”

In her dissertation, Gillian Poulter notes that Canadian newspapers

sometimes described the sensation of tobogganing for women in what she

described as “surprisingly eroticised terms”. The Brookline News, in an

article on tobogganing published on Christmas Day, 1886, was more

circumspect:. “There are some things about it [tobogganing],” wrote the

News, “that never will and never can get into any newspaper.”

The

same article in the News did include a description of another part of

tobogganing with particular appeal for young couples: the climb together

back up the hill. The article quoted a pamphlet on tobogganing,

together with an illustration of “The Uphill Road,”:

"Uphill we clambered, and as I felt the gloved hand of Dick’s younger sister upon my sustaining arm, I wished the climb might have been twice the distance; and right here I want to say that if ever a woman looks fresh and young and irresistibly lovely it is when at the top of a climb up a toboggan slide she stops with her cheeks flushed, her lips parted, and her eyes shining with the exertion [of the climb].”

In January 1888, the Brookline News shared what a couple of magazines had to say about what was on the minds of young couples on the Corey Hill slopes:

"Puck [a humor magazine) says if you have the right kind of girl, the walk up the toboggan slide is just as exciting as the ride down. And sometimes more so. It's a glorious sport both ways."

- Brookline News, January 14, 1888

“Ethel: Which toboggan slide do you like best, Corey’s Hill or Wright’s Hill?

Mabel: Oh ! Corey’s Hill, don’t you? It’s so much steeper that the men have to hold on to – er – the toboggans ever so much tighter.”

- Brookline News, January 21, 1888 (Reprinted from the Harvard Lampoon)

Tobogganing Seasons Come and Gone

Club members and their guests continued to climb Corey Hill to use the club’s chutes through the winter of 1894-95. Many more came out to watch. As many as 500 people were reported on the slopes at times, with as many as 150 actually going down the chutes.

A good tobogganing season depended, of course, on having enough snow. Activity rarely began before January, and there were years where very little tobogganing took place. (A January 28, 1888, Brookline Chronicle article noted there had been 30 nights of tobogganing so far that season and that they hoped to break the previous records of 55 nights.)

Social events at the clubhouse were a big part of the Corey Hill Toboggan Club’s activities, whether there was actually tobogganing or not. There were musical performances by club members, “smokers” (probably male-only social gatherings) and “ladies’ nights.”

There were carnivals on the slopes, modeled on those that were held in Montreal and elsewhere. (The 1893-94 season, for example, included an “Illumination Night,” with fireworks, fire balloons and bonfires, and a “Fancy Dress Carnival.”) In the last years of the club, these social events received more attention in the local press than the actual tobogganing.

The winter of 1894-95 was the last to see tobogganing on the chutes of the Corey Hill Toboggan Club. In December 1895, the Brookline Chronicle reported that the club was planning several elaborate entertainments for the next three or four months. But on January 18, 1896, the Chronicle asked “What is the matter with the Corey Hill Toboggan Club this winter? Will the gentle art of harmless chuteing [sic] be allowed to become extinct?”

That same week, the Boston Post, in a brief article titled “Tobogganing on Corey Hill,” reported:

“The lovers of tobogganing in the city will probably not have a chance this winter to enjoy the sport at the Corey Hill Toboggan Club. The chute is all falling to pieces and ditches are dug through the field where the chute makes its course.

A meeting of the directors of the Corey Hill Club was held last Christmas, but nothing definite was done in regard to fixing up the slide. "

The demise of the Corey Hill Toboggan Club was no doubt due to growing residential development in this part of Brookline in the wake of the laying out of the Beacon Street boulevard and the coming of the streetcar a decade earlier.

By 1897, the club, it’s clubhouse, and its celebrated toboggan chutes were no more. (See the maps below for a detailed view of the change.)

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Brookline History Through Digitized Newspapers

Did you know that ...

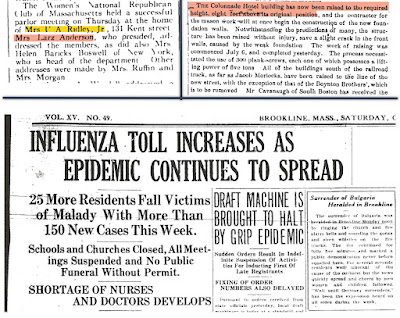

...Florida Ruffin Ridley and Isabel Anderson spoke together at a political meeting at the Ridley home on Kent Street in 1912?

...the Colonnade buildings in Brookline Village, built in the 1870s, were raised eight feet in 1886 to accommodate a new bridge over the railroad tracks (now the MBTA D Line)?

...the 1918 flu pandemic closed Brookline schools, caused a shortage of medical personnel, and led to numerous deaths in town.

These are just a few of the many pieces -- large and small -- of Brookline's past that are now more easily accessible thanks to the Brookline Library's digitization of more than 70 years (1870-1941) of local newspapers.

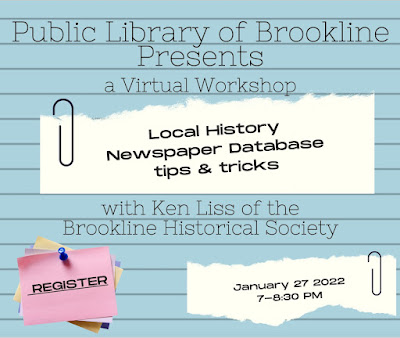

Learn how to make the most of the Library's online newspaper database at a virtual workshop on Thursday, January 27th, from 7:00 to 8:30 pm.

The 90-minute workshop will provide tips and tricks for making the most of this valuable resources for uncovering and understanding facts about people, places, and events from the town's past.

|

| Examples of articles in the digitized newspaper database of the Public Library of Brookline (Click image for larger view) |