Henry Hudson Kitson and Theo Alice Ruggles at work in their studio in 1893. This sketch, which first appeared in The Illustrated American, was reproduced in a June 25, 1893 Boston Globe article—"Tale of Art and Love"—that described their partnership and forthcoming marriage. (Click on image for a larger view.)

Henry Hudson Kitson and Theo Alice Ruggles at work in their studio in 1893. This sketch, which first appeared in The Illustrated American, was reproduced in a June 25, 1893 Boston Globe article—"Tale of Art and Love"—that described their partnership and forthcoming marriage. (Click on image for a larger view.)In 1885, 14-year old Theo Alice Ruggles made a snow sculpture in the yard of her family's Brookline home on Harvey Street (now 30 Upland Road). This was no ordinary snowman. It showed a recumbent horse in the act of rising from the ground, and it attracted notice in the neighborhood and beyond. People from Boston were said to make the trip out to Brookline just to see it.

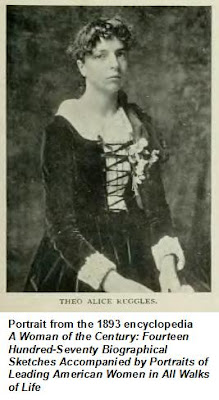

Encouraged by admiring visitors, Ruggles' parents tried unsuccessfully to enroll her in art school before finding a young sculptor, Henry Hudson Kitson, willing to take her on as a student. It marked the beginning of a journey that would lead in just a few years to the Paris Salon, to partnership and marriage with Kitson, and to recognition as one of the most accomplished woman sculptors of her day.

Perhaps most remarkably for a woman in that era, Theo Ruggles Kitson became one of the leading sculptors of war memorials in the United States, with statues, busts, and reliefs on display from coast to coast commemorating the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, and World War I.

Perhaps most remarkably for a woman in that era, Theo Ruggles Kitson became one of the leading sculptors of war memorials in the United States, with statues, busts, and reliefs on display from coast to coast commemorating the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, and World War I.Theo Alice Ruggles was born January 29, 1871. She was the daughter of Cyrus W. and Anna H. Ruggles. Her father, a successful businessman, was also Brookline's postmaster and the station master in town for the Boston & Albany Railroad. As a young girl, Theo enjoyed sculpting images out of clay at the family's summer home and letting them bake in the sun.

In the wake of the attention the snow sculpture brought to Ruggles and her work that winter of 1885 her parents sought a place for her in the school of the Museum of Fine Arts. The school turned her down as too young, as did other art schools and several private tutors.

Henry Hudson Kitson, who became her teacher and later her husband, was a native of England who had come to the United States as a teenager. He was 20 years old when he began working with Ruggles. When a commission took Kitson to Paris in 1887, his young student—accompanied by her mother—followed so that she could continue her studies.

Henry Hudson Kitson, who became her teacher and later her husband, was a native of England who had come to the United States as a teenager. He was 20 years old when he began working with Ruggles. When a commission took Kitson to Paris in 1887, his young student—accompanied by her mother—followed so that she could continue her studies.In Paris, Ruggles learned from and worked with Kitson and also studied with French artists, including Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret and Gustave Courtois. In 1888, she had one of her sculptures accepted for the Paris Salon and the following year, while still a teenager, she became the first American woman sculptor to receive an award at the Salon.

Kitson and Ruggles were married in 1893, after their return to the United States. She had four works exhibited that year at the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago. In 1895, she became the first woman (and youngest member) in the new National Sculpture Society.

A Harper's magazine profile published that year said of her:

Though one of the youngest women who are known through their work in the art world, Mrs. Kitson has had the most successful career of any woman who has undertaken the profession of sculpture.

Theo Ruggles Kitson (as she became known) completed her first military sculpture—a statue of Revolutionary War naval hero Esek Hopkins in Providence, Rhode Island—in 1897.

Theo Ruggles Kitson (as she became known) completed her first military sculpture—a statue of Revolutionary War naval hero Esek Hopkins in Providence, Rhode Island—in 1897.Her 1902 Civil War monument ("The Volunteer") in Newburyport, Massachusetts became the model for the Massachusetts memorial at the Vicksburg National Military Park in Mississippi (shown at left). The first monument erected at Vicksburg, it was also the first of more than 60 statues, busts, and reliefs created by Kitson for the Vicksburg park between 1903 and 1920 .

The Boston Globe saw "The Volunteer" as a new kind of statue:

....a departure from the conventional soldier, which stands on a variety of pedestals in cemeteries and parks at 'present arms' or some other parade ground attitude. The figure is as much a departure from such figures as is the real American volunteer soldier from all previous soldiers in any land.

This spirit of volunteerism, continued the Globe,

is manifest in every line of the figure and it is really remarkable that a woman should be the first to note and portray in sculpture this strong characteristic of the American volunteer soldier, when it is the very thing that every foreign military critic first notices and always has noticed and commented upon. The trouble has been that the traditional solider of sculpture has been too hard to pull away from and Mrs. Kitson was the first who had the courage to give exact expression to the very qualities for which the volunteer soldier has always stood.

Author Polly Welts Kaufman, in her book National Parks and the Woman's Voice: A History (University of New Mexico Press, 2006), saw a different motivation in her description of the dedication of the Vicksburg statue :

Theo Kitson saw her Civil War sculptures as providing an opportunity for reconciliation and healing, not for the commemoration of heroism. Kitson herself was chosen to unveil the statue, but she insisted that a Confederate woman assist her in the unveiling. Alice Cole, the daughter of a Confederate soldier, joined her.

Kitson was also responsible for the first Civil War monument to feature a woman serving the troops. A memorial to nurse Mary Bickerdyke showing "Mother Bickerdyke" serving water to a wounded Union soldier, it stands in Galesburg, Illinois.

Theo Ruggles Kitson's statue of Civil War nurse Mary Bickerdyke stands in front of the courthouse in Galeburg, Illinois.

Theo Ruggles Kitson's statue of Civil War nurse Mary Bickerdyke stands in front of the courthouse in Galeburg, Illinois.In 1904, Kitson received a commission from the University of Minnesota for a statue memorializing graduates of the university who were killed in the Spanish-American War. Dedicated in 1906, it became known as "The Hiker." The Gorham Company of Rhode Island made dozens of casts of this statue, including some after Kitson's death. Examples of "The Hiker" can be found today in several New England cities and towns and in other parts of the country, including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, Maryland, Louisiana, Tennessee, Ohio, Michigan, Texas, Arizona, and California.

Other examples of Kitson's work in Boston include memorials to Thaddeus Kosciuszko in the Public Garden and (with her husband) to Patrick Collins, second Irish-American mayor of Boston, in the Back Bay.

Theo and Henry Kitson separated in 1909, though they never divorced. She continued to work, out of studios in Framingham and elsewhere. She also contributed, along with other notable women, to columns in the Boston Globe about such issues as women's education. Theo Ruggles Kitson died in Boston in 1932.

Additional Photo Credits

"The Volunteer"

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kenlund/ / CC BY-SA 2.0

Bickerdyke Memorial

http://civilwarwomen.blogspot.com/2008/08/mary-ann-ball-bickerdyke.html

"The Hiker"

Bickerdyke Memorial

http://civilwarwomen.blogspot.com/2008/08/mary-ann-ball-bickerdyke.html

"The Hiker"