NOTE: This is an expanded version, with illustrations, of an article that first appeared in the Brookline TAB

and its Wicked Local Web site.

Brookline’s 1884 memorial to its Civil War dead was restored, reinstalled, and rededicated in the lobby of Town Hall on Memorial Day. If you haven’t gone to see it, you should.

|

| Photo courtesy of Jesse Mermell |

Unlike the town’s more visible statue of an anonymous bugler on his horse, these seven tablets of pink Tennessee marble pay tribute to individual men, their names chiseled into stone along with their units and the dates and places of their deaths.

There are 72 in all, soldiers and sailors who died at such places as Antietam, Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, and the notorious Confederate prison at Andersonville, Georgia.

A century and a half ago, news of these storied places arrived in Brookline not just as part of the broad saga of the war but also as terrible news for families living in streets (and maybe a few houses) that are familiar to us today. That gives more meaning to the names of these places and takes us back to Brookline at the time of the Civil War.

Inspired by the rededication, I’ve been digging deeper, piecing together fragments that tell who these men were and what happened to them. A few—officers and members of prominent families—were easy; their stories were documented at the time and have been preserved in books, letters, and other sources.

|

Wilder Dwight, 18622

(Click for larger view) |

Wilder Dwight, for example, was a Harvard-educated lawyer and a lieutenant colonel in the infantry. Mortally wounded at Antietam but in too much pain to be moved, he lay on the ground as battle raged around him and added these words to a letter, stained with his blood, that he had begun writing that morning:

DEAREST MOTHER,--I am wounded so as to be helpless. Good by, if so it must be. I think I die in victory. God defend our country. I trust in God, and love you all to the last. Our troops have left the part of the field where I lay.1

On the opposite page he added “All is well with those that have faith.” Dwight was carried to the rear that evening and died the following day at age 29. He was buried in Forest Hills Cemetery, along with his brother, Howard, who was killed in Louisiana eight months later.

|

| Charles L. Chandler3 |

Charles L. Chandler, a civil engineer, was a lieutenant colonel of Massachusetts troops. Wounded in Virginia in May 1864, he fell into Confederate hands. Two weeks later, his mother Eliza received a letter from a fellow officer that told how, under a flag of truce, a Confederate colonel came to him with news of Chandler’s death.

He lived for some hours [the officer wrote], and was kindly cared for by Colonel Harris, who has his watch, money, diary, and photograph of young lady. . . Colonel Harris said, Lieutenant-Colonel Chandler died happy, and desired him to give his love, etc., to all his family and friends.3

Chandler’s belongings were returned to his family after the war, but his body was never recovered. He was 24 years old when he died.

|

This painting, "Even To Hell Itself" by Donna J. Neary, shows Lt. Col. Charles L. Chandler, center, in the action at the North Anna River in Virginia where he was mortally wounded. It was made for the North Anna Battlefield Park. Used by permission of the artist.

Credit: Donna J. Neary, Heritage Studio |

Unlike Dwight and Chandler, most of the men whose names are on the memorial were working men—carpenters, blacksmiths, laborers, shoemakers, and clerks—including several Irish immigrants and sons of immigrants.

|

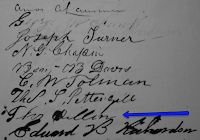

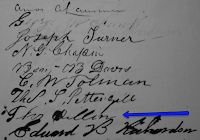

| Thomas Dillon's signature4 |

Thomas Dillon came to Brookline from Armagh, Ireland. A teamster like his father, he enlisted in Wilder Dwight’s regiment in 1862 at age 31 and, like Dwight, was killed at Antietam. Dillon’s company commander remembered:

One of the men of my company killed at Sharpsburgh, the other day, lived in Brookline, and had been out here only about six weeks; his name was Thomas Dillon, and he was a good, faithful fellow...A letter came for him two days after his death, which I think, under the circumstances, was one of the most affecting things I ever read... I do not know of anything that has brought the horrors of the war more plainly before me than this letter. I have written to the father of Dillon, telling him of his son's death.5

Daniel Webster Atkinson, a 25-year old journeyman carpenter, fell during the siege of Petersburg in October 1864. Atkinson was a tall man with blue eyes, light hair, and fair skin, according to an August 1862 list of enrollees in the 10th Battery of Massachusetts Light Artillery. (At six-feet one-and-a-quarter inches, Atkinson was the tallest of the 26 men listed and one of only two over six feet.)

John Billings, a comrade who wrote a history of the regiment, called Atkinson

.... a brave soldier, a professed Christian and true man...As the troops halted from time to time, he was several times seen, apart from the column, reading the Scriptures, or on his knees in prayer.6

Atkinson, wrote Billings, escaped serious injury in July 1864 when he fell asleep and walked off a pontoon bridge while crossing the Appomattox River "providentially alighting in one of the boats" supporting the bridge.

His luck ran out three months later at Hatcher's Run, Virginia, where he was shot and killed and "thus sealed with his blood the cause he had upheld from the beginning with peculiar earnestness." Atkinson, noted Billings, had told fellow soldiers he did not expect to survive the war and, on the morning of the day he died "had given directions to some of his more intimate comrades in regard to the disposal of his effects in case he should fall."

|

| Site of the action in which Daniel Atkinson was killed, as it looked in 1896. From Billings' History of the Tenth Massachusetts Battery of Light Artillery in the War of the Rebellion, p. 366. |

Five months after the battle, Billings and his fellow artillerymen passed by the place where Atkinson had fallen and found a grave on the spot.

Satisfied that it was his, there being no others near, we hastily inscribed his name, battery, and date of death on a rough board, with satisfaction at being thus able to mark his remains for future removal, before passing on with the column.

John W. Clark was one of the older Brookline men to die in the war. A mason, he was 39 when he enlisted in September 1861. After the battle of Antietam Clark’s unit was recuperating with others in Bakersville, Maryland, when President Lincoln came to review the troops and receive their cheers. It’s unlikely that Clark saw him. Diarrhea caused by water from a stream that ran through the camp had put many of the troops on sick call, and Clark was probably among them. He died of disease two days after Lincoln’s visit.

The only son of the pastor of Brookline’s Baptist Church,

Samuel Lamson was a 23-year-old paymaster’s clerk on board the paddlewheel steamboat

Ruth as it came down the Mississippi River in August 1863 carrying soldiers, civilians, and two and a half million dollars in cash — the payroll for General Grant’s army besieging Vicksburg. Near Cairo, Illinois, the steamer caught fire and sank. (Sabotage was suspected.) Twenty-six people died. Two eyewitnesses recalled seeing Lamson, who couldn’t swim, jumping reluctantly into the water clutching a window shutter. His body was recovered two weeks later.

|

| The burning of the steamer Ruth as shown in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper |

These are just six of the Brookline men who died in the Civil War. (Stories of some of the others will be forthcoming.) I wish I could learn more about how they lived, not just how they died. But the restored memorial keeps their names alive, and telling their stories reminds us how deeply Brookline was affected by the war and what the town lost 150 years ago.

NOTES

1Life and Letters of Wilder Dwight, Lieut.-Col, Second Mass. Inf. Vols. (1868)

2Sketch of Wilder Dwight drawn by Private Francis D'Avignon, a French-born artist serving with the First Massachusetts Infantry. Image source:

Heritage Auctions

3Lt.-Col. Charles Lyon Chandler (1864)

4On April 22, 1861 -- 10 days after the attack on Fort Sumter and three days after a mob of Confederate sympathizers attacked a Massachusetts regiment as it passed through Baltimore -- more than 200 Brookline men enrolled "for the purpose of acquiring a knowledge of military drill and discipline" offered by the town. Dillon was one of the first to sign up. A little over a year later he enlisted in the Second Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.

5Letter from Charles Fessenden Morse, September 26, 1862, in

Letters Written During the Civil War, 1861-1865 (1898)

6The History of the Tenth Massachusetts Battery of Light Artillery in the War of the Rebellion. Formerly of the Third Corps, and afterwards of Hancock's Second Corps, Army of the Potomac. 1862-1865 (1881) [Photo is from 1909 edition]