|

| Roland Hayes (Credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection) |

I had to leave before the Hayes Project was recognized, but I heard later that Hayes was said to be the first African-American to purchase property in Brookline. I wondered: Is that true?

Many people, places, and events are said to be the first this or the oldest that. But the facts are often not that clear. There are doubters and disputants, caveats and qualifiers, questions and counter-claims.

First Things First?

Marblehead and Beverly, for example, have had a long-running debate over which is the birthplace of the American Navy. (The Navy says neither one is right.) No less than half a dozen communities (four of them in New England) have been cited as having the oldest public library in the United States. (Brookline’s library makes no such claim, but is said to be “the first to be organized under May 1851 state legislation allowing communities to tax themselves for such purposes.” Whew! There’s a qualifier for you.)

When I was a Boston tour guide, I learned to describe Old Ironsides, the U.S.S. Constitution in Charlestown, as “the oldest commissioned warship afloat in the world.” There are older warships still afloat, but they are not still commissioned in their nation’s navies, as is the Constitution. There’s an older commissioned warship: Admiral Nelson’s flagship H.M.S. Victory predates the Constitution by 38 years and is still commissioned in the Royal Navy. But it’s not afloat; it’s kept in drydock in Portsmouth, England. Got that?

Now, it doesn’t really matter whether Roland Hayes was the first, the third, the eighth or the 80th African-American to purchase property in Brookline. His legacy is secure, as is the dedication of the Hayes Project and Brookline to celebrate his talent and his musical and social struggles and accomplishments.

But my skepticism about historical firsts and my love of research led me to look deeper, and, as is often the case, my digging turned up much more than the answer to a single question.

Brookline, Race, and the Historical Record

I went through Census records, town directories, property maps, and newspaper archives. I “met” other African-American residents from Brookline’s past. And I opened a window, if only a crack, into ways of learning more about an aspect of Brookline’s history that is often overlooked.

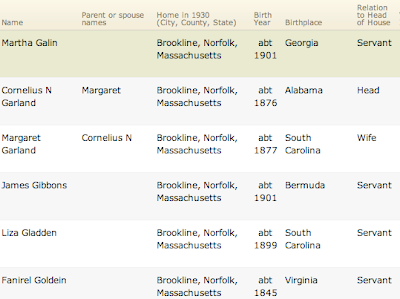

I started with the 1930 U.S. Census, the first to show Roland Hayes in Brookline. Records from the Census list 296 Brookline residents of the “Negro” race, out of a total population of 47,579 in 1930. (Racial classification underwent a major change with the 1930 Census. See this Wikipedia article for a brief overview of race and ethnicity in the U.S. Census' history)

About two-thirds of those listed as Negro in the Census that year were servants of one kind or another, living with other families and thus not homeowners themselves. (A portion of the search results, via Ancestry.com, is shown below.) A few were shown as lodgers or boarders. Most of the rest were heads of households or their family members.

|

| A portion of the list of Brookline residents classified as "Negro" in the 1930 U.S. Census, as obtained by a search in Ancestry.com |

Samuel Davis and the Coolidge Corner Garage

Brookline town directories are available in Ancestry.com (and in the Brookline Room of the main library). I went back to 1924, the year before Roland Hayes purchased the home at 58 Allerton Street and moved to Brookline. I found Samuel A. Davis of 39 Marion Street, one of the six African-American homeowners from 1930, already there.

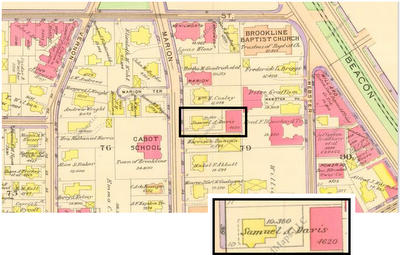

In fact, directories, maps, and deeds show Davis and his wife Mary at the Marion Street home as early as 1913 and at his adjacent business, the Coolidge Corner Garage, as early as 1907, nearly two decades before Hayes purchased his Brookline home.

|

| This 1913 map shows the property of Samuel A. Davis on Marion Street. The yellow (woodframe) building is the home of Davis and his wife Mary at 39 Marion Street. The pink (brick) building at the back of the property is his business, the Coolidge Corner Garage. Credit: WardMaps.com |

Davis is intriguing. Neither well-known or well-documented, he was an African-American homeowner and the proprietor of an auto garage at a time when very few African-Americans owned homes or businesses in Brookline. (Auto garages were a new but growing presence on the scene in 1907. Four years later, Davis' garage was one of eight in town providing charging stations for electric vehicles. See my earlier post.) I'm doing further research and hope to tell more of Davis' story soon.

But Samuel and Mary Davis were not the first African-Americans to own property in Brookline either.

A Home on Kent Street at the Turn of the Century

|

| 131 Kent Street was the home of Ulysses and Florida Ridley from the 1890s to the 1920s. Credit: Town of Brookline |

Ulysses Ridley was a successful Boston tailor. Florida Ruffin Ridley was a member of a prominent African-American family in Boston. Her father, George Lewis Ruffin, was the first black graduate of Harvard Law School and served as a judge and a member of both the Massachusetts legislature and the Boston Common Council. Her mother, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, was a writer, editor, and organizer who became especially active on behalf of women's rights, education, and the advancement of African-Americans after the death of her husband in 1886.

|

| This sketch of Florida Ruffin Ridley appeared with an article written by her in the Boston Globe in 1894. Credit: Boston Globe |

The First? ... Or Not?

So...

...were the Ridleys, who lived on Kent Street from 1896 until the early 1920s, the first African-American homeowners in Brookline?

Well, maybe. I could not find any others in the U.S. Census records from 1850-1880. (The 1890 records were destroyed in a fire.) But there is not enough information in pre-1850 Census records and, of course, the Census records do not cover the years between each decennial Census. Plus, Brookline existed as an independent town for 85 years before the first Census in 1790.

Were there other African-American homeowners in Brookline before the Ridleys? I'll have to dig deeper to try to find out. I may or may not succeed. But like most such efforts, that research is bound to lead to other paths and other discoveries along the way.