The jar was recently offered for sale online with no date of origin and little description. Some quick research turned up an advertisement (below right) from the June-July 1914 issue of American Cookery magazine, and the jar was acquired for the Historical Society.

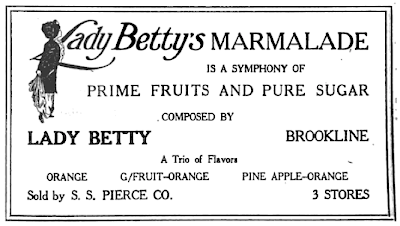

But who was “Lady Betty”? The address — “Beacon and Washington Sts.” — gave just a clue. A second advertisement from 1914, a musically-themed ad in the program of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, was a treat to find but offered no further hints to the identity of “Lady Betty.”

Finally, a third 1914 ad was found in the December issue of Good Housekeeping magazine, and this one had a specific address: 1624 Beacon Street.

1624 Beacon Street was (and still is) part of the Rhodes Block, a commercial building on the northeast corner of Washington Square, built in 1913 for the Rhodes Brothers grocery store. (A branch of Rhodes Brothers occupied the corner location.) 1624 was one of two storefronts on the Beacon Street side of the building; there were two more on the Washington Street side.

|

| The Rhodes Block in 1914. (From The Brookline Christmas Magazine, published by the Brookline Friendly Society, December 1914). 1624 Beacon is at the far right. |

Cleveland Circle Travel occupies the 1624 storefront today. But a look at the 1914 Brookline Directory gave us the answer we were looking for. “Lady Betty” was actually a woman named Gertrude Maynard.

Gertrude Maynard was born Gertrude Maria Davis in Vermont in 1847. She married Abbott Thayer Maynard in Boston in 1869. Abbott Maynard was a jeweler and silversmith with a business on Boylston Street in Boston for many years.

The Maynards moved from Boston to Brookline around 1908. (That’s the first year they were listed in town directories.) It’s unclear when Gertrude Maynard began producing her Lady Betty line of products, but it was no later than 1912. The ad below for Park & Tilford, one of Lady Betty's retail outlets, appeared in the December 19, 1912 edition of the Evening Herald in New York.

Ads for Lady Betty products appeared in several other newspapers and magazines as well. The products were sold in stores in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and Detroit, and by mail order. They were exhibited at the Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915.

Maynard advertised her products as “Guaranteed free from adulteration. No artificial color, flavor, or preservatives.” As proof, she cited approval from two leaders in the pure food movement of the time: Lewis B. Allyn and Harvey W. Wiley. Allyn was a professor of chemistry at the Westfield Normal School in Westfield, MA who established the Westfield Standard for food purity and evaluated thousands of food products.

Wiley, also a chemist, played a leading role in the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906 and became the first commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. In 1912, he resigned to take over leadership of Good Housekeeping magazine’s food testing laboratories.

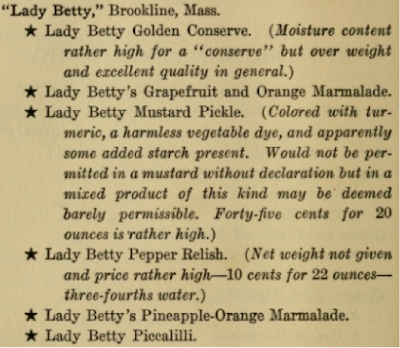

Wiley’s 1916 book 1,001 Tests of Food, Beverages and Toilet Accessories, Good and Otherwise: Why They Are So included analysis of several Lady Betty products. All received his star rating, or stamp of approval, but not without some comment on the ingredients—and the high prices Lady Betty charged.

Gertrude Maynard died in September 1916 at age 69. The business may have continued for a while after her death. (Abbott Maynard, who had retired from the jewelry business, was listed in town directories as a manager at 1624 Beacon as late as 1919.)

In any case, this Brookline business started by a woman in her 60s was a short-lived one. But “Lady Betty” now lives on in the collection of the Brookline Historical Society.

|

| Life magazine, April 9, 1914 |

|

| Washington Post, October 30, 1913 |

|

| Wellesley Townsman, June 8, 1917 |