Agnes Nolan was one of 18 children of a Brookline letter carrier and his wife. Her father had his moment in the spotlight in 1905 when no less a figure than President Theodore Roosevelt intervened after John Nolan lost his post office job (and source of support for his large family).

But the real celebrities in the Brookline family were Agnes and three of her eight sisters, all of whom appeared on stage.

Agnes and her sisters Lola, Alice, and Grace were all members of the company of “Yankee Doodle Dandy” George M. Cohan—arguably the most popular entertainer of the period. Agnes' stage career was brief, but she made big news locally and nationally in 1907 when she and Cohan were married.

The marriage—his second and her first—was planned, fittingly enough, for the Fourth of July though it actually occurred on June 29th.

The Nolans of Brookline

John J. Nolan began working for the postal service in Brookline in 1875. He was reportedly the first to deliver mail directly to individual homes in town. (Prior to 1864 postage only paid for post office-to-post office delivery; home delivery began in the big cities and spread slowly to other communities after the Civil War.)

Nolan was also the one to lay out the routes Brookline letter carriers used when free home delivery finally reached town.

In 1899, however, Nolan was dismissed from the postal service for drunkenness. As his son-in-law,

Boston American columnist George Holland later described it:

The appropriate figure of speech would be to say that he had crooked his elbow.

Perhaps we could blame it on the monotony of trudging up to the same front doors.

A swinging door was different. Off his route, John Nolan found swinging doors and they opened on a warming atmosphere where, for a time, one could relinquish the responsibilities that came with the largest family in New England.

Whether or not it was the largest in New England, Nolan's family was certainly large. He and his wife Mary had 18 children (17 according to some accounts). Three died very young, but all of the others—with 29 years separating the oldest and youngest—lived with their parents in a succession of Brookline homes.

They were at 116 Brooks Street in 1900 and 38 Gorham Avenue in 1903. Later Brookline addresses for the parents included 149 Winthrop Road and 19 Green Street.

Nolan went to work in the coal business after his dismissal from the postal service, but his plight eventually came to the attention of U.S. Congressman Samuel Powers in whose district the Nolans lived. Powers brought the case to the attention of President Roosevelt in the White House, noting that:

It is claimed that the Department at the time of his discharge promised to reinstate him if his subsequent conduct should justify such action. The accompanying letters and certificates conclusively show that Nolan has been absolutely free from habits of intoxication ever since his discharge.

The congressman also enclosed a photo of the family, which he had advised Nolan to have taken, to show the president that Nolan "is not an adherent to any doctrine of race suicide."

(Roosevelt was said to be obsessed with the concept of "race suicide" a concern that English-speaking whites, through declining birth rates, were not keeping up with immigrants and other minorities. See Chapter VII, "Race Suicide," in

Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race by Thomas G. Dyer, LSU Press, 1992).

In March 1905, Roosevelt issued an order reinstating Nolan to the postal service. According to Holland, the president telephoned the postmaster personally and Nolan was back on the job the next day.

The Nolan Daughters on Stage

By 1905, Lola, Agnes, and Alice Nolan, who began their performing careers under the stage name of the Merrill Sisters, were part of George M. Cohan's theater company.

Cohan has been called the father of the American musical comedy and "the man who owned Broadway." After beginning his career in vaudeville with his parents and sister, performing as The Four Cohans, he turned to the theater in 1901.

A writer, director, and performer, he produced more than 80 Broadway shows and wrote more than 1,500 songs over four decades.

Lola joined Cohan's company first. Agnes and Alice auditioned for the 1904 New York production of "Little Johnny Jones," Cohan's first Broadway hit. (It was the show that introduced such standards as "Yankee Doodle Boy" and "Give My Regards to Broadway.")

Cohan was reportedly smitten with Agnes' vitality—and the audacity she showed in asking for $25 a week for chorus work, more than the going rate. She and Alice were added to the company. (A fourth sister, Grace, later worked for Cohan as well.)

In February 1907, Cohan divorced his wife, the actress Ethel Levey. In April, it was announced that he and Agnes Nolan would be married on July 4th, Cohan's purported birthday. (Birth records show that he was born on July 3rd, but the "Yankee Doodle Boy" always claimed he was "born on the Fourth of July.")

In the end, the marriage took place a few days ahead of schedule, in Freehold, New Jersey, before a justice of the peace. As the

New York Times reported on June 30, 1907:

An automobile accident last Monday detained the couple, who were taking a short trip, for several hours in Freehold, and during that time they decided to get married. They returned to Freehold yesterday and were married by the justice.

Agnes's sister Alice and Cohan's long-time partner, producer Sam Harris, were the only witnesses. Alice Nolan and Sam Harris would marry later that year, and the two couples would build adjacent homes in Great Neck on Long Island.

Agnes Cohan, conforming to the wishes of her husband and her parents, retired from the stage after her marriage. She and Cohan had a son and two daughters.

In 1942, Warner Brothers released

Yankee Doodle Dandy, a musical biography of Cohan that won a Best Actor Oscar for James Cagney. Agnes Cohan was not a character in the movie. Cohan had stipulated that the film make no mention of his first wife Ethel Levey, and the filmmakers instead created a composite of the two wives to serve as Cohan's love interest in the picture.

The film was shown to the Cohans in a private screening. George was ill with cancer; he died in November of that year at age 64.

Agnes Cohan outlived her husband by nearly 30 years. She died September 10, 1972 at the age of 89. She had been living in Queens in obscurity and in poor health for 10 years. Neighbors told the

New York Times she was devoted to television and had few visitors other than family. Most of the neighbors did not know who she was.

Times reporter Laurie Johnston described Agnes Cohan's funeral. About 60 people attended the service at Our Lady of Martyrs Catholic church in Queens in contrast, noted Johnston, to the thousands who filled the streets around St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan for George Cohan's funeral.

"I wanted to see if there were any celebrities," whispered a woman in purple wool as she slid into a pew and dropped to her knees beside a friend [wrote Johnston]. She was to be disappointed.

A few years before Agnes Cohan's death, the musical biography

George M. opened on Broadway. (Joel Grey, like Cagney before him, won a Best Actor award—a Tony—for his portrayal of Cohan.) Agnes Nolan Cohan, as well as Ethel Levey, were restored as characters in the play.

In a 1970 television version of the play, Agnes was played by Blythe Danner, better know to today's audiences, perhaps, as the mother of Gwynneth Paltrow.

Agnes Nolan's mother Mary died in 1921 and her father John in 1929. Several other members of the Nolan family, in addition to the four sisters, had careers or ties to the entertainment industry.

- Alice Nolan Harris last appeared on stage in a Cohan revue in 1910. She died in 1930 at the age of 42.

- Loretta (Lola) Nolan, who continued to use the stage name Lola Merrill, married the actor Frank Otto and appeared in an act with him for many years, often in Cohan and Harris productions. The last surviving of the many Nolan children, she died in 1974.

- Grace Nolan Landy had a brief acting career. She died in 1938 at the age of 47.

- John F. Nolan, the oldest son, worked in the Boston post office for 28 years before leaving in 1913 to manage the Cohan and Harris Theater in New York. He died in 1923.

- Raymond Nolan (1893-1967) moved to California and was a still photographer for 20th Century Fox Studios for many years.

- William Nolan (1892-1953) was an editor at the Douglas Fairbanks Studio and worked on several Fairbanks films including The Thief of Baghdad.

- Dorothy Nolan Holland (1895-1971), the youngest child, married George Holland who was a playwright and longtime "Boston After Dark" columnist for the Boston American. They continued to live in Brookline.

- Another brother, Matthew Nolan (1879-1955), also remained in Brookline. He was not in the entertainment business; he was a Brookline firefighter for 45 years before retiring as Acting Deputy Chief in 1947.

Boston was the Hub of bicycling in the United States in the 1880s. The Boston Bicycling Club, the first in the country, was founded in 1878. Five years later, Outing, a Journal of Recreation labeled the city "the bicycling paradise of America." Wheelmen, as they were sometimes called, came from all over to ride "the beautiful roads that have rendered Boston the metropolis of bicycling."

Boston was the Hub of bicycling in the United States in the 1880s. The Boston Bicycling Club, the first in the country, was founded in 1878. Five years later, Outing, a Journal of Recreation labeled the city "the bicycling paradise of America." Wheelmen, as they were sometimes called, came from all over to ride "the beautiful roads that have rendered Boston the metropolis of bicycling."

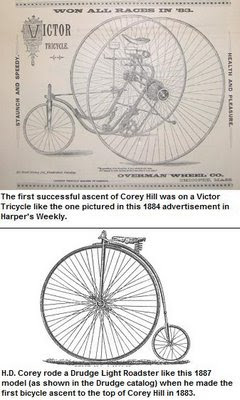

W.W. Stall, a Boston bicycle and tricycle dealer, was the first to make it to the top, in July 1883. He rode a Victor Tricycle like the one shown in the ad at left.

W.W. Stall, a Boston bicycle and tricycle dealer, was the first to make it to the top, in July 1883. He rode a Victor Tricycle like the one shown in the ad at left.