Dr. Cornelius N. Garland, a pioneering Black physician and the founder of the first and only Black hospital in Boston, spent the last 24 years of his life in Brookline, where he lived on Corey Hill from 1928 to 1952.

Garland's story was featured earlier this month in a piece on Cognoscenti, WBUR's ideas and commentary site, and an interview aired on Radio Boston. The author of the Cognoscenti article, Lisa Gordon, was joined on Radio Boston by Garland's great grandson Dan Reppert.

Gordon began digging into the story while living in an apartment in the South End building that had been Garland's hospital. She and Reppert told how the Alabama native founded Plymouth Hospital in 1908. The hospital employed Black doctors and included a training program for nurses at a time when city hospitals would neither employ Black physicians nor admit Black women to their nursing programs.

The Plymouth Hospital and Nurses Training School continued to operate until 1928. Garland hoped to expand his efforts with a second hospital and had support from the community. His plan was opposed, however, by influential Boston Guardian publisher William Monroe Trotter. Trotter, reported Gordon, "believed a second Black-only hospital would perpetuate existing racial problems" and, instead, "vehemently advocated to integrate city hospitals, starting with Boston City Hospital."

Garland, added Gordon, "recognized that he and Trotter had a similar goal: equity for the Black community." He joined Trotter in lobbying for the integration of Boston City Hospital, "perhaps believing both plans could work in tandem." In 1928, he closed Plymouth Hospital. One year later, City Hospital admitted its first Black students, although it would be 20 years before the first Black physician was added to the staff.

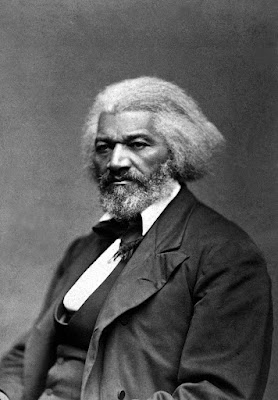

Dr. Garland in Brookline

Cornelius and Margaret Garland lived on West Canton Street in the South End, on the edge of the Back Bay and a 15 minute walk from Plymouth Hospital. In December 1928, after the closing of the hospital, they purchased a newly-built home at 173 Mason Terrace in Brookline. (The deed was in Margaret's name.)

Their daughter, Thelma, then 26, was a French teacher in Baltimore at the time and did not live with her parents in Brookline. (Thelma married James Kelly Smith in August 1929.)

Garland continued to practice medicine in Boston out of an office at the West Canton Street brownstone, while renting the rest of their former home to tenants. He was also involved in many health, social, business, and political organizations and activities, both before and after moving to Brookline.

He was heavily involved in the work of the Boston Tuberculosis Association, promoting good home hygiene practices as a way of combating the disease. (The Boston Globe, in 1937, reported that one section of Roxbury "at one time had the highest mortality rate in the country for Negroes suffering from tuberculosis," but had seen a big improvement in recent years.)

You can learn much more about Cornelius Garland, his family, and Plymouth Hospital from the following sources:

- "Boston's Only Black Hospital Was Founded in 1908." Lisa Gordon, Cognoscenti, February 9, 2023

- "The Hidden History of Boston's First and Only Black Hospital." (Interview with Lisa Gordon and Dan Reppert). Radio Boston, February 13, 2023

- "Dr. Garland and Plymouth Hospital." Alison Barnet, Aceso: The Journal of the Boston University School of Medicine Historical Society. (The article begins on page 50 of the issue.)