(In honor of the Opening Day of the 2010 baseball season, Muddy River Musings looks at George Wright, the only member of the Baseball Hall of Fame buried in Brookline.)

(In honor of the Opening Day of the 2010 baseball season, Muddy River Musings looks at George Wright, the only member of the Baseball Hall of Fame buried in Brookline.)

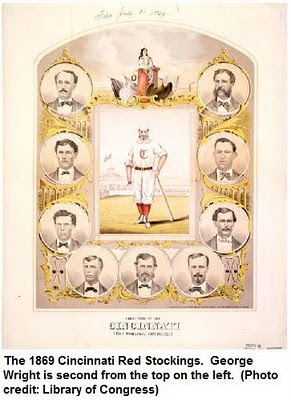

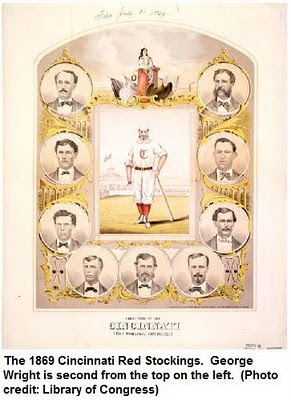

Baseball Hall of Famer George Wright, who is buried in Holyhood Cemetery in Brookline (although he never lived in Brookline), was perhaps the game's first real star. He was the shortstop and leading hitter on the undefeated Cincinnati Red Stockings of 1869, the first all-professional baseball team.

He moved to Boston in 1871 with the Red Stockings and his older brother Harry—captain and manager of the team—and won five league championships with Boston.

Wright was also an ambassador for the game. He was part of two teams that helped bring the game to the West in the 1860s. He joined trips to England in 1874 and around the world in 1888 to demonstrate the sport. Wright even umpired an exhibition game at the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden.

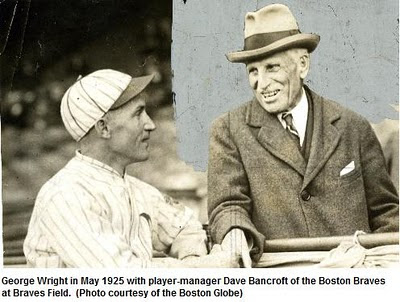

But his accomplishments in the national pastime, which earned him selection to the Hall of Fame soon after his death in 1937, don't tell the whole story of George Wright's impact on American sports.

Wright had a long post-baseball career as one of the nation's top cricket players at the Longwood Cricket Club in Brookline. As head of the Wright & Ditson sporting goods company in Boston, he helped popularize both tennis and ice hockey in the United States.

Perhaps most significantly, Wright played a key role in introducing golf to the U.S. and was sometimes called "the father of American golf."

Born Into a Sporting Family

George Wright was born in New York City in 1847. His father Sam, a professional cricket player, had emigrated from England in 1836 with his wife Annie and their young son Harry. The family moved to Hoboken, New Jersey in 1857, and the Wright brothers played cricket and the new game of "base ball" on the Elysian Fields of that city.

Starting at age 15, Wright played with baseball teams from New York, Philadelphia, and Washington. In 1867, he was on the Washington Nationals team that made the first tour of an eastern club to the cities of the "West": Columbus, Louisville, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis. Among the teams they beat (by a score of 53-10) was brother Harry's Cincinnati Red Stockings. (Harry had gone to Cincinnati in 1865 to manage a cricket club, but was soon leading one of the city's top baseball teams as well.)

Determined to match the powerful eastern teams, Harry Wright and Red Stockings owner Aaron Champion brought together the first all-professional—or at least first

openly all-professional—team for the 1869 season. George Wright, signed to play shortstop, was the highest paid player with an annual salary of $1,400. Wright, reported the

St. Louis Republican, was

the beau-ideal of base-ball players. His fielding exhibits science at every point, his picking, throwing and strategy could not be excelled, and he is plucky in facing balls of every description.

The Red Stockings went through the 1869 season undefeated. They were invited to the White House to meet with President Grant. In September they traveled to California for games on the West Coast. (The Transcontinental Railroad had only been completed a few months before. The players reportedly slept with pistols under their pillows out of fear of Indian attacks on the train.)

After another successful season in 1870, the Cincinnati club broke up. Harry Wright started a new team in Boston, bringing along brother George and several other players (as well as the Red Stockings name.) The team dominated the National Association, sometimes considered the first professional baseball league, winning the championship in all five years of its existence (1871-1875), before joining the new National League in 1876.

George Wright left the Boston team to lead the rival Providence club in 1878. He ended his National League career in 1882.

Beyond Baseball: Man of Many Sports

Not long after coming to Boston, Wright went into the sporting goods business as a sidelight to his athletic career. Joining forces with fellow merchant Henry Ditson, he built a successful business that lasted long after the end of his playing career. (Wright & Ditson was eventually absorbed into the sporting goods empire of Wright's former Boston teammate A.G. Spalding.)

Wright & Ditson carried equipment for all kinds of sporting and recreational activities popular with Americans. But it also brought Wright into contact with new kinds of athletic endeavors, most notably the game of golf, largely unknown in America at the time.

Wright's first exposure to golf came when he ordered a set of clubs and balls from an English catalog. They arrived without rules or instructions, and Wright, with no knowledge of the game, left them on display in his store on Washington Street in Boston. There they caught the eye of a visiting Scotsman who explained the game and later sent Wright a copy of the rules.

In December 1890, Wright and a group of friends set out for Franklin Park to try the game. Stopped by a policeman, they obtained a permit from the parks commission and returned, laying out a nine-hole course using tomato cans for the holes. They played two rounds, reportedly the first rounds of golf ever played in New England.

A few years later, Franklin Park became the site of the

second municipal golf course in the U.S., still in use today. Another municipal course, designed by Donald Ross in Hyde Park in the 1930s, was named the

George Wright Golf Course in honor of Wright's pioneering promotion of the sport.)

Wright & Ditson became a leading seller of golf clubs. Brookline's Francis Ouimet got his first club from Wright & Ditson. (His older brother Wilfred traded used golf balls for the club.) In 1911, Ouimet got a job as a clerk at Wright's store, and Wright was generous in his support of the young golfer's burgeoning amateur career.

By the time Francis came to work for him [wrote Mark Frost in The Greatest Game Ever Played], George Wright knew all about the young man's potential in the game and took a personal interest in the ex-Country Club caddie. As a former professional athlete, he understood only too well the pressures a gifted young player faced as he neared adulthood, searching for the limits of how far his talent could take him.

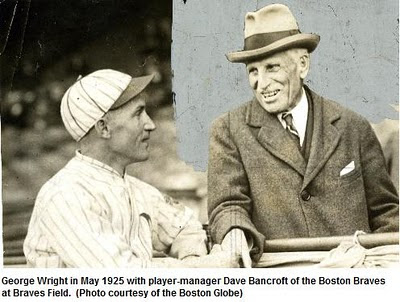

Wright, who had given his young clerk time off from the store, was in the gallery in Brookline in 1913 when Ouimet won his historic upset victory over Britons Harry Vardon and Ted Ray at the U.S Open at the Country Club. He continued to promote (and play) golf into his 80s.

Wright's interest in athletics extended into other sports as well.

In 1894, Wright helped organize a set of ice hockey and ice polo matches in Canada between Canadian athletes and a team of U.S. collegians from Harvard, Yale, Brown, and Cornell. (Ice polo, popular in the U.S., was similar to hockey but played with rounded mallets and a rubber ball.)

After watching a few contests [wrote David Fleitz in More Ghosts in the Gallery], George recognized that hockey was the superior game, so he set his company to work promoting the Canadian sport and manufacturing its equipment. By the dawn of the 20th century, hockey had supplanted ice polo in popularity, with George Wright providing a major impetus to its growth in the United States.

In 1898, Wright brought a group of top Eastern tennis players to California to help promote the sport on the West Coast. The players included Dwight Davis, for whom the Davis Cup is named, as well as Holcombe Ward and Brookline's Malcolm Whitman. (Ward and Whitman would be Davis' teammates on the first Davis Cup squad in 1900.) Also on the trip was Wright's son Beals who was then the national interscholastic champion and would, like the other three, later be elected to the International Tennis Hall of Fame. (Wright's son Irving was also a tennis player and served as president of the Longwood Cricket Club.)

Baseball Ambassador

While exploring, promoting, and playing other sports, Wright remained closely involved with baseball. As noted above, he was part of two early trips to the West in the 1860s to help promote the game. In 1874, the Wright brothers joined Albert Spalding, their Boston Red Stockings teammates, and the Philadephia Athletics on a trip to England to demonstrate the American game. (Old cricketers George and Harry Wright also helped the Americans surprise local cricket teams by beating them at their own game.)

Wright joined Spalding again in 1888-89 for a celebrated round-the-world barnstorming trip that brought baseball to Australia, Ceylon, Egypt, Italy, France, England, and Ireland. (Wright helped build a canvas batting cage on board ship so the players could practice without losing balls overboard.)

In 1912, the Swedish hosts of the Summer Olympic Games in Stockholm asked the American Olympic Committee to arrange an exhibition baseball game against a Swedish team. The Americans secured uniforms and equipment for two teams. Players were recruited from the American track and field athletes. George Wright, then 65, was brought along as umpire and coach.

The playing of the exhibition games had to wait until the American athletes were finished competing in their events. Jim Thorpe, fresh off his gold medal wins in the pentathalon and decathalon, played in the second of the two games.

Wright, in addition to umpiring the first game, helped coach the Swedish players in the finer points of baseball.

Wright was a member of the Mills Commission which in 1908 famously and erroneously attributed the invention of baseball to Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, New York in 1839. As Dan Okrent and Steve Wulf wrote in their book

Baseball Anecdotes, Wright should have known better. On the other hand, it is likely that Wright's presence on the Mills Commission was largely symbolic. According to Okrent and Wulf, he never attended any of the meetings.

He did continue attending games, including a return to Cincinnati during the 1919 World Series. He became the oldest living ex-major leaguer in 1935.

George Wright died at his home Dorchester on August 21, 1937 at the age of 90. He was buried in Holyhood Cemetery in Brookline. Four months after his death, Wright was selected to the Baseball Hall of Fame as one of the pioneers of the game.