If you missed my 9/15 conversation with WBUR’s Sharon Brody about Commonwealth Avenue’s Automobile Row in Boston and Brookline, the talk/slideshow is now available on the station's YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYpoghQ1laU&t=1s

Sunday, September 29, 2019

Monday, May 27, 2019

Old Sprinkler Alarms in Brookline & Beyond

As with many of my projects, this one started with a question. I posted this image of a 1930s Brookline storefront (299 Harvard Street) to Twitter and Facebook in July 2018, and a follower asked:

I found another image of the same location from the late 50s or early 60s, when it was the celebrated deli Jack and Marion's. There was the same round object.

Then I went to the site — now the Gen Sou En Japanese tea house — for a closer look.

Seeing the object — on a column at the right side of the building — showed that my initial suspicion that it was some kind of an alarm was right. Imprinted around the top edge of the cast iron bell was the name of a Worcester-based company: Rockwood Sprinkler Co.

Rockwood, founded in 1906, made fire protection sprinkler systems and alarm gongs designed to be set off whenever the sprinklers were activated. Their Worcester plant is now an arts center called — what else? — The Sprinkler Factory.

Sprinkler alarms are nothing unusual. You'll see plenty of them, in Brookline and elsewhere. Most are solid steel discs, usually painted red, sometimes with a light as well as a gong.

But this was different. It was made of iron. It had a symmetrical pattern of holes, both decorative and designed to help spread the sound. It was an industrial artifact I had passed by thousands of times without noticing it. I was intrigued.

Then I started noticing more of them, of different designs, around town.

Now, almost a year later, I've launched a website featuring my virtual collection of cast iron sprinkler alarms. Take a look — it's at https://bit.ly/sprinkler-alarms — for more about these bits of industrial archaeology in Brookline and beyond.

What is the, uh, circle thing, that's on the right side of the building that's been there all along (and is still there today)?

|

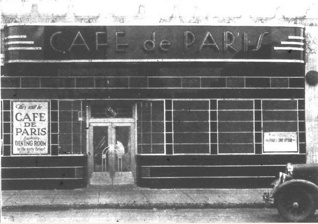

| Image from an advertisement for the Cafe de Paris. Brookline Chronicle, November 29, 1934 |

Then I went to the site — now the Gen Sou En Japanese tea house — for a closer look.

Seeing the object — on a column at the right side of the building — showed that my initial suspicion that it was some kind of an alarm was right. Imprinted around the top edge of the cast iron bell was the name of a Worcester-based company: Rockwood Sprinkler Co.

Rockwood, founded in 1906, made fire protection sprinkler systems and alarm gongs designed to be set off whenever the sprinklers were activated. Their Worcester plant is now an arts center called — what else? — The Sprinkler Factory.

Sprinkler alarms are nothing unusual. You'll see plenty of them, in Brookline and elsewhere. Most are solid steel discs, usually painted red, sometimes with a light as well as a gong.

|

| Modern sprinkler alarms in Brookline |

But this was different. It was made of iron. It had a symmetrical pattern of holes, both decorative and designed to help spread the sound. It was an industrial artifact I had passed by thousands of times without noticing it. I was intrigued.

Then I started noticing more of them, of different designs, around town.

Now, almost a year later, I've launched a website featuring my virtual collection of cast iron sprinkler alarms. Take a look — it's at https://bit.ly/sprinkler-alarms — for more about these bits of industrial archaeology in Brookline and beyond.

Sunday, February 17, 2019

Booze on the Border? Brookline Says No

As Brookline's (and metro Boston's) first recreational marijuana dispensary gets closer to opening (see Brookline Patch and Wicked Local Brookline), Muddy River Musings looks back at another local battle over the sale of intoxicating substances.

It happened nearly a century and a quarter ago not far from the site, at the corner of Washington and Boylston Streets, where New England Treatment Access (NETA) is getting ready to add recreational sales to the medical marijuana dispensary it has operated since 2016.

The year was 1895 and the issue was a group of four saloons just over the Brookline border on Heath Street (now South Huntington Avenue) in Boston. Brookline was a dry town at the time, and had been since 1887 when Town Meeting voted 452-268 to ban the granting of licenses for the sale of intoxicating beverages.

The oldest of the disputed establishments, John Devine's tavern and dealership at 368 Heath Street (see the photo below) had been in business for 20 years. James Pendergast's saloon, at 380 Heath, had been around for 15 years. But the presence of these and other saloons so close to a town that had banned liquor sales a few years earlier clearly rankled the town's leaders.

A parade of speakers — including the current and former chairs of the Board of Selectmen and the head of the School Committee — testified before the police board at a hearing in late April.

There was also an underlying, if unspoken, class and ethnic dimension to the protests. The Heath Street taverns were closest to the working class, largely Irish Brookline neighborhoods of The Farm and The Marsh north and south of lower Washington Street (Route 9). As Ronald Dale Karr points out in his 2018 book Between City and Country: Brookline, Massachusetts and the Origins of Suburbia, the arrival of the Irish had changed the emphasis of the local temperance movement "from exhorting individual abstinence to outlawing public drinking."

This was the focus of the local chapter of the Women's Christian Temperance Union, established in 1877. The existence of the taverns just over the border —as well as the existence of illegal rum shops in the Irish neighborhoods — presented a continuing challenge after the local liquor ban was enacted in 1885.

A week after the April 1895 hearing the police board handed down its verdict: the Heath Street saloons would have to go. (There was speculation at the time that the decision was made in part to circumvent a more far-reaching legislative mandate like the one that had been proposed by Brookline's Utley.)

The four tavern owners were granted time to find alternative locations further from the Brookline border. They would be allowed to keep their liquor licenses as long as they found other locations in which to operate.

In early November 1895, after a meeting between the liquor dealers, the Brookline men, and the police board, it was announced that November 9th would be the last day the taverns could operate on Heath Street. Two of the owners had found new locations in Roxbury and one in South Boston. The fourth was still looking for a site.

The local newspaper, the Brookline Chronicle, treated the news as a victory for the town. The Boston Globe was more sympathetic to the tavern owners. In a November 10th article with the headline "Too Close to Brookline People," the Globe noted that

John Devine and his wife Annie, whose business is pictured in the photo shown above, applied in December 1895 to have their liquor license transferred from 368 Heath Street to 80 Longwood Avenue. The new location (now McGreevey Way) was a couple of blocks southeast of Huntington Avenue near the McCormick and Continental breweries.

It's not clear if the application was granted, but even if it was they were not on Longwood Avenue for long. In March 1896, the Devines (operating as John Devine & Co.) filed successfully for a license "to sell intoxicating liquors as Victuallers of the First Class and Wholesale Dealers of the Fourth Class" at 29 Eustis Street in Roxbury.

John Devine, however, did not live to long enough to see how well the business would do in its new location. He died in October 1896, less than a year after being forced to move his tavern from its longtime location just across the Muddy River from Brookline. His age was estimated at 62. The business continued under his wife Annie and a woman named Maria O'Brien.

As for Brookline, it continued to vote every year to maintain the ban on the selling of liquor within town boundaries (and, presumably, to oppose such establishments near its borders as well). The town did vote to go "wet" again in March 1920, but that vote was symbolic only; Prohibition had gone into effect nationally two months earlier.

It would be another 13 years until, with Prohibition winding down, Brookline's long liquor ban would come to an end. (See 1933: After 46 Years, Beer Back in Brookline for more on that story.)

It happened nearly a century and a quarter ago not far from the site, at the corner of Washington and Boylston Streets, where New England Treatment Access (NETA) is getting ready to add recreational sales to the medical marijuana dispensary it has operated since 2016.

The year was 1895 and the issue was a group of four saloons just over the Brookline border on Heath Street (now South Huntington Avenue) in Boston. Brookline was a dry town at the time, and had been since 1887 when Town Meeting voted 452-268 to ban the granting of licenses for the sale of intoxicating beverages.

The oldest of the disputed establishments, John Devine's tavern and dealership at 368 Heath Street (see the photo below) had been in business for 20 years. James Pendergast's saloon, at 380 Heath, had been around for 15 years. But the presence of these and other saloons so close to a town that had banned liquor sales a few years earlier clearly rankled the town's leaders.

A parade of speakers — including the current and former chairs of the Board of Selectmen and the head of the School Committee — testified before the police board at a hearing in late April.

There was also an underlying, if unspoken, class and ethnic dimension to the protests. The Heath Street taverns were closest to the working class, largely Irish Brookline neighborhoods of The Farm and The Marsh north and south of lower Washington Street (Route 9). As Ronald Dale Karr points out in his 2018 book Between City and Country: Brookline, Massachusetts and the Origins of Suburbia, the arrival of the Irish had changed the emphasis of the local temperance movement "from exhorting individual abstinence to outlawing public drinking."

This was the focus of the local chapter of the Women's Christian Temperance Union, established in 1877. The existence of the taverns just over the border —as well as the existence of illegal rum shops in the Irish neighborhoods — presented a continuing challenge after the local liquor ban was enacted in 1885.

A week after the April 1895 hearing the police board handed down its verdict: the Heath Street saloons would have to go. (There was speculation at the time that the decision was made in part to circumvent a more far-reaching legislative mandate like the one that had been proposed by Brookline's Utley.)

The four tavern owners were granted time to find alternative locations further from the Brookline border. They would be allowed to keep their liquor licenses as long as they found other locations in which to operate.

In early November 1895, after a meeting between the liquor dealers, the Brookline men, and the police board, it was announced that November 9th would be the last day the taverns could operate on Heath Street. Two of the owners had found new locations in Roxbury and one in South Boston. The fourth was still looking for a site.

|

| Boston Globe November 10, 1895 |

"The proprietors entered 'willingly' into the arrangement, it is stated at police headquarters, but in reality it was very reluctantly, because they had no other resource if they wanted to continue to sell liquor."

John Devine and his wife Annie, whose business is pictured in the photo shown above, applied in December 1895 to have their liquor license transferred from 368 Heath Street to 80 Longwood Avenue. The new location (now McGreevey Way) was a couple of blocks southeast of Huntington Avenue near the McCormick and Continental breweries.

It's not clear if the application was granted, but even if it was they were not on Longwood Avenue for long. In March 1896, the Devines (operating as John Devine & Co.) filed successfully for a license "to sell intoxicating liquors as Victuallers of the First Class and Wholesale Dealers of the Fourth Class" at 29 Eustis Street in Roxbury.

John Devine, however, did not live to long enough to see how well the business would do in its new location. He died in October 1896, less than a year after being forced to move his tavern from its longtime location just across the Muddy River from Brookline. His age was estimated at 62. The business continued under his wife Annie and a woman named Maria O'Brien.

As for Brookline, it continued to vote every year to maintain the ban on the selling of liquor within town boundaries (and, presumably, to oppose such establishments near its borders as well). The town did vote to go "wet" again in March 1920, but that vote was symbolic only; Prohibition had gone into effect nationally two months earlier.

It would be another 13 years until, with Prohibition winding down, Brookline's long liquor ban would come to an end. (See 1933: After 46 Years, Beer Back in Brookline for more on that story.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)