February 14th is Douglass Day, an annual celebration of the life of Frederick Douglass. This year the Public Library of Brookline is participating by hosting a public transcribe-a-thon, where community members can help bring different aspects of Black history to light.

This year's project is working on the papers of Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893), an activist, journalist, publisher, teacher, and lawyer, and one of the earliest Black women to edit a newspaper. Volunteers can join the project anytime between 12 and 3 pm on February 14th, in person at the library or online. For details, see the library website.

|

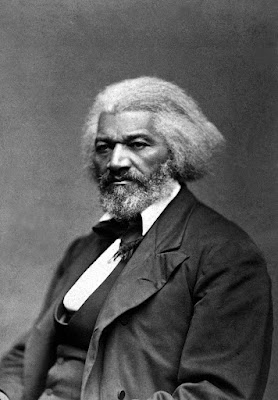

| Frederick Douglass in 1879. (National Archives) |

Frederick Douglass spoke in Brookline in December 1874, as part of a lecture series at the then new Town Hall, which had been dedicated one year earlier. The series was organized by James Redpath, a journalist and, before the Civil War, an anti-slavery activist. Redpath formed a well-known, Boston-based speaker's bureau that was active across the U.S. for many years after the war.

|

| This advertisement for James Redpath's lecture series at Brookline Town Hall appeared in the Boston Journal on August 22, 1874. |

Local cotton merchant Zenas Brett, whose 1874 diary was transcribed by students at the then Edward Devotion School (now the Florida Ruffin Ridley School) in 2005, attended Douglass' lecture and made this note in the diary:

"Wife + I went to hear Frederick Douglass lecture this eve in our Town Hall subject. 'John Brown' "

Though Brett's description is brief (and typical of his diary entries), there is a lengthy description of the same speech as given by Douglass three months earlier in Rochester, NY, where he lived for many years. Douglass, according to the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, said he came to vindicate Brown

"....a great historic character of our own time and country--one with whom it had been his fortune to be well acquainted and whose friendship it had been his pleasure to share. And in so doing he would endeavor to throw a more favorable light on the great event of the Harpers Ferry raid ... [and its role in] the thirty years struggle between slavery and liberty...."

Douglass had taken to the lecture circuit to help with what historian John R. McKivigan has described as an existential and vocational post-war crisis brought on by "a pressing need for revenue, not just to support himself, but to assist his four adult children and their growing families financially." 1

At the same time, Douglass was concerned that audiences came to see him as almost what we would describe today as a novelty act. "I shall never get beyond Fred Douglass the self educated fugitive slave," he wrote to Redpath in 1871, adding that

"I shall endeavor not to forget that people do not attend lectures to hear statesmanlike addresses, which are usually rather heavy for the stomachs of young and old who listen. People want to be amused as well as instructed. They come as often for the former as the latter, and perhaps as often to see the man as for either."

No comments:

Post a Comment